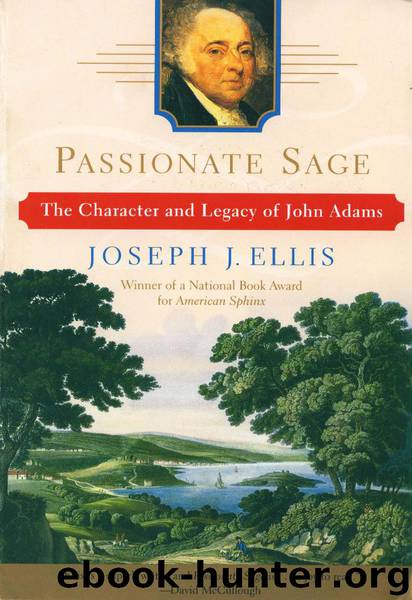

Passionate Sage by Joseph J. Ellis

Author:Joseph J. Ellis

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

Published: 2001-02-14T16:00:00+00:00

The thrust of John Taylor’s long-winded and much-delayed critique of Adams’s Defence was to argue that, apart from specific disagreements about the power of the presidency and the role of the Senate, Adams’s entire way of thinking about politics was hopelessly out of date and, in the end, fundamentally un-American. Taylor apologized for the twenty-year delay in getting his own thoughts into print, claiming that he had waited “until age had abated temporal interests and diminished youthful prejudices.” He acknowledged that, given his own and Adams’s advancing years, his published thoughts “are almost letters from the dead.” Although the tone of Taylor’s remarks was not personal—he was properly respectful toward one of the nation’s patriarchs and claimed to have “a high opinion of his virtue and talents”—the message of Taylor’s book was devastating. If Taylor was right, Adams was an intellectual anachronism who had missed the political significance and meaning of the American Revolution.18

For his part, Adams let it be known that he was not going to defer gracefully or apologetically, nor had age diminished his vaunted capacity to defend himself. “You must allow me twenty years to answer a book that cost you twenty years of meditation to compose,” he warned Taylor. One could hear the rounds clicking into Adams’s chambers and the salvo being aimed toward Caroline County. He expressed the hope that Taylor’s work would not burden him with “the absurd criticism, the stupid observations, the jesuitical subtleties, the stupid lies that have been printed concerning my writings, in this my dear, native country, for five and twenty years….” If so, Taylor should expect no quarter from the self-professed “Hermit of Quincy.”19

The core of Taylor’s critique was to charge that Adams was the prisoner of a classical way of thinking about politics that was no longer appropriate for post-revolutionary America. What Taylor called “the numerical analysis” was the classical assumption that all political arrangements were variations on the same eternal theme: namely, the proper balancing of the interests of the one, the few, and the many. In the Defence, this ancient formula had caused Adams to adopt the old classical categories of monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy. Because Adams’s mind remained trapped “within the magick circle of the numerical analysis,” he had failed to recognize that the American Revolution had changed everything. “Monarchy, aristocracy and democracy” were not timeless truths, but “rude, and almost savage political fabricks.” Constructing a new constitution for America with these elements was “like…erecting a palace with materials drawn from Indian cabins.” Adams might be excused for thinking in the old way and offering readers “a cloud of quotations…collected from the deepest tints of ancient obscurity.” After all, he had been abroad in France and England for most of the 1780s, when American political thinking “had advanced more rapidly…than the philosophy and policy comprising his references had in twenty centuries.” But, excuses aside, Adams continued to live and think within a classical paradigm that had been blown to pieces by the democratic and egalitarian implications of the very revolution he had done so much to foster.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| U.K. Prime Ministers | U.S. Presidents |

Waking Up in Heaven: A True Story of Brokenness, Heaven, and Life Again by McVea Crystal & Tresniowski Alex(37815)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23090)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19055)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(18596)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13342)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12036)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8403)

Educated by Tara Westover(8061)

How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life by Lilly Singh(7495)

Permanent Record by Edward Snowden(5852)

The Last Black Unicorn by Tiffany Haddish(5643)

The Rise and Fall of Senator Joe McCarthy by James Cross Giblin(5284)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5157)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5104)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4967)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4821)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4367)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4119)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3973)